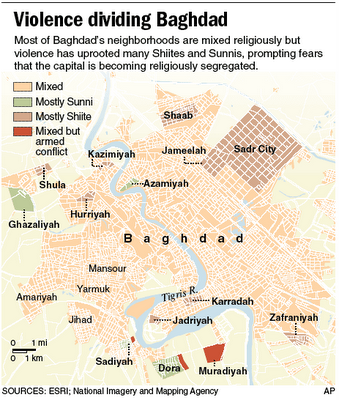

...moving toward Sunni west and a Shiite east, with the broad Tigris River snaking through the middle as the sectarian boundary

population of more than 6 million,

The mixed character of some neighborhoods, such as Jihad and Amariyah, is partly due to Saddam Hussein’s policy of rewarding government officials and Baath Party figures.

The rifts widened dramatically this year. After a Feb. 22 blast destroyed an important Shiite shrine in Samarra, Shiite hard-liners stopped listening to their clerics’ appeals for restraint.

The core fight today is a struggle for control of the corridors into the city from the north and south.

In the north, Shiites control an arc of neighborhoods — Sadr City, Kazimiyah and Shula.

In the south, Sunni militants are trying to consolidate power in another arc, comprised of Sadiyah and Dora.

The anchor of Shiite power is Sadr City in northeastern Baghdad. It’s an almost exclusively Shiite community of 2.5 million people that is the stronghold of radical cleric Muqtada al-Sadr, head of an important militia called the Mahdi army.

Al-Sadr is a key supporter of Prime Minister Nouri al-Maliki, and the prime minister angrily criticized the Americans for using excessive force in a joint U.S.-Iraqi raid on Sadr City in early August.

From Sadr City, Mahdi militiamen fan out across eastern Baghdad and use major traffic arteries such as Palestine Street to reach religiously mixed areas to the south and east. That gives them a degree of control along the eastern and northern routes into the city — and they’re trying to strengthen that control.

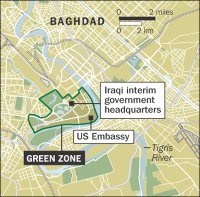

Sparsely populated areas just outside Sadr City also are good locations for firing mortars and rockets at the U.S.-controlled Green Zone

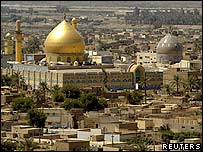

Shiite stronghold — Kazimiyah — a neighborhood that grew up around the shrine of an 8th century Shiite saint.

Shula, a haven for Shiites driven from their homes elsewhere.

But wedged between Sadr City and Kazimiyah is a cluster of Sunni districts, chief among them Azamiyah, where Saddam hid when Baghdad fell to U.S. forces in April 2003. Azamiyah thus prevents Shiite extremists from moving freely between Sadr City and the two other Shiite strongholds to the west.

Sunnis in Azamiyah have formed armed neighborhood militias to guard against outsiders

When Iraqi government police entered the area last April to set up checkpoints, many Azamiyah residents were convinced that Shiite death squads would not be far behind. The Sunni groups battled government forces for two days.

southern rim, lies another key flashpoint — where Sunnis are pressing to consolidate power over the mixed, but mostly Sunni, neighborhoods of Dora and Sadiyah.

The arc they form along a bend in the Tigris River is another key point of control. It’s a route that Shiite pilgrims travel between Baghdad and a religious shrine to the south. But it also connects Baghdad to a belt of Sunni villages where al-Qaida and other Sunni religious extremists operate — an area known as the “Triangle of Death” for its frequent attacks.

In this area, Dora is the prize. A once-fashionable neighborhood of spacious villas and leafy streets, Sunni extremists have been violently pressuring Shiites and Christians to leave.

Sunni control of Dora also threatens Karradah, a mostly Shiite district across the Tigris that is controlled by the country’s biggest Shiite party. In late July, about 30 people were killed in Karradah in a coordinated attack of car bombs and a rocket barrage fired across the river from Dora.

Abu Saleh, a retired Agriculture Ministry official, moved from Shula, in the Shiite area, to Sadiyah in July after he and his wife were verbally harassed as “defiled Sunnis.”

No comments:

Post a Comment