Pakistan: Unveiling the Mystery of Balochistan Insurgency - Part One

NewsTariq Saeedi in Ashgabat

With Sergi Pyatakov in Moscow, Ali Nasimzadeh in Zahidan, Qasim Jan in Kandahar and S M Kasi in Quetta

Additional reporting by Rupa Kival in New Delhi and Mark Davidson in Washington

Deception and treachery. Live and let die. The ultimate zero sum game. Repetition of bloody history: Call it what you may, something is happening in the Pakistani province of Balochistan that defies comprehension on any conventional scale.

Four correspondents and dozens of associates who collectively logged more than 5000 kilometers during the past seven weeks in pursuit of a single question – What is happening in Balochistan? – have only been able to uncover small parts of the entire picture.

However, if the parts have any proportional resemblance to the whole, it is a frightening and mind-boggling picture.

Every story must start somewhere. This story should conveniently have started on the night of 7 January 2005 when gas installations at Sui were rocketed and much of Pakistan came to almost grinding halt for about a week. Or, we should have taken the night of 2 January 2005 as the starting point when an unfortunate female doctor was reportedly gang-raped in Sui. However, the appropriate point to peg this story is January 2002 and we shall return to it in a minute.

Actually, the elements for the start of insurgency in Balochistan had been put in place already and the planners were waiting for a convenient catalyst to set things in motion. The gang-rape of 2 Jan, around which this sticky situation has been built, was just the missing ingredient the planners needed.

Two former KGB officers explained that the whole phenomenon has been assembled on skilful manipulation of circumstances. We shall keep returning to their comments throughout this report.

As Pakistan and India continue to mend fences, as Iran, Pakistan and India try to pool efforts to put a shared gas pipeline, as Pakistan, Afghanistan and Turkmenistan join hands to lay a natural gas pipeline of great economic and strategic importance, as the United States continues to laud the role of Pakistan as a frontline nation in war against terrorism, as Chinese contractors forge ahead with construction work in Gawadar port and on trans-Balochistan highway, as the Pakistan government makes efforts to bring Balochistan under the rule of law and eliminate safe havens for terrorists and drug barons, as the whole region tries to develop new long-term models to curb terrorism and bring prosperity to far flung areas, there is a deadly game going on in the barren and hostile hills of Balochistan. Liens are muddy; there are no clear-cut sectors to distinguish friends from foes.

Right in the beginning we would like to clarify that when we say Indians, we mean some Indians and not the Indian government because we don’t have any way of ascertaining whether the activities of some Indian nationals in Pakistan represent the official policy of their government or is it merely the adventurism of some individuals or organizations. When we say Iranians or Afghans, we mean just that: Some Iranians or Afghans. We don’t even know whether the Iranian and Afghan players in Balochistan are trying to serve the interests of their countries or whether their loyalties lie elsewhere.

But – and it is a BUT with capital letters – when we say Americans or Russians, we have reasons to suspect that the American and Russian involvement in Balochistan is sanctioned, at least in part, by Pentagon (if not White House) and Kremlin.

We would also like to acknowledge that the picture we have gathered is far from complete and except for the explanatory comments of two former KGB officials, we have no way of connecting the dots in any meaningful sequence. For the sake of honesty, this story should better remain abrupt and incomplete.

The story we are going to tell may sound a lot like cheap whodunit but that is what we found out there.

Before zooming in to January 2002, let’s set the background.

We consulted Sasha and Misha, two former KGB officers who are Afghanists – the veterans of Russo-Afghan war – and they seem to know Balochistan better than most Pakistanis. Obviously, Sasha and Misha are not their real names. They live on the same street in one of the quieter suburbs of Moscow. Two bonds tie them together in their retirement: While on active duty in KGB, they were both frequent travelers to Balochistan during the Russo-Afghan war where they were tasked to foment trouble in Pakistan; and they are both wary of Vodka, the mandatory nectar of Russian cloak and dagger community. They visit each other almost every day and that is why it was easy to catch them together for long chats over quantities of green tea and occasional bowls of Borsch.

We made more than a dozen visits to the single-bedroom flat of Misha, where Sasha was also found more often than not, and we picked their brains on Balochistan situation. As and when we unearthed new information on Balochistan, we returned to Sasha and Misha for comments.

As they told us, during the Russo-Afghan war, the Soviet Union was surprised by the ability and resourcefulness of Pakistan to generate a quick and effective resistance movement in Afghanistan. To punish Pakistan and to answer back in the same currency, Kremlin decided to create some organizations that would specialize in sabotage activities in Pakistan. One such organization was BLA (Balochistan Liberation Army), the brainchild of KGB that was built around the core of BSO (Baloch Students Organization). BSO was a group of assorted left-wing students in Quetta and some other cities of Balochistan.

Misha and Sasha can be considered among the architects of the original BLA.

The BLA they created remained active during the Russo-Afghan war and then it disappeared from the surface, mostly because its main source of funding – the Soviet Union – disappeared from the scene.

In the wake of 9-11, when the United States came rushing to Afghanistan with little preparation and less insight, the need was felt immediately to create sources of information and action that should be independent of the government of Pakistan.

As Bush peered into the soul of Putin and found him a good guy, Rumefeld also did his own peering into the soul of his Russian counterpart and found him a good game. The result was extensive and generous consultation by Russian veterans who knew more about Afghanistan and Balochistan than the Americans could hope to find.

It was presumably agreed that as long as their interests did not clash with each other directly, the United States (or at least Pentagon) and Kremlin would cooperate with each other in Balochistan.

That brings us to January 2002.

“Actually, most of the elements were in place, though dormant, and it was not difficult for anyone with sufficient resources to reactivate the whole thing,” said Misha about the present-day BLA that is blamed for most of the sabotage activities in Balochistan.

In January 2002, the first batch of ‘instructors’ crossed over from Afghanistan into Pakistan to set-up the first training camp. That was the seed from which the present insurgency has sprouted.

It seemed like a modest effort back then.

Only two Indians, two Americans, and their Afghan driver-guide were in a faded brown Toyota Hilux double cabin SUV that crossed the border near Rashid Qila in Afghanistan and came to Muslim Bagh in Pakistani province of Balochistan on 17 January 2002. For this part of the journey, they used irregular trails. From Muslim Bagh to Kohlu they followed the regular but less-frequented roads.

In Kohlu they met with some Baloch youth and one American stayed in Kohlu while two Indians and one American went to Dera Bugti and returned after a few days. They spent the next couple of weeks in intense consultations with some Baloch activists and their mentors and then the work started for setting up a camp.

“Balch was one of our good boys and even though I don’t know who the present operators are, it can be said safely that Kohlu must have been picked as the first base because of Balach,” said Misha.

Balach Marri is the son of Nawab Khair Bakhsh Marri and he qualified as electronic engineer from Moscow. As was customary during those times, any Baloch students in Russia were cultivated actively and lavishly by the KGB. Balach was one of their success stories.

Because of intimate connections with India and Russia, it was no surprise that Balach Marri was picked as the new head of the revived BLA. The mountains between Kohlu and Kahan belong to the Marris.

The first camp had some 30 youth and initial classes comprised mainly of indoctrination lectures. The main subjects were: 1. Baloch’s right of independence, 2. The Concept of Greater Balochistan, 3. Sabotage as a tool for political struggle, 4. Tyranny of Punjab and plight of oppressed nations, and 5. Media-friendly methods of mass protest.

“Manuals, guidelines and even lecture plans were available in the Kometit [KGB] archives. Except for media interaction, they virtually followed the old plans,” told Sasha.

As was logical, the small arms and sabotage training soon entered the syllabus. First shipment of arms and ammunition was received from Afghanistan but as the number of camps grew, new supply routes were opened from India.

Kishangarh is a small Indian town, barely five kilometers from Pakistan border where the provinces of Punjab and Sindh meet. There is a supply depot and a training centre there that maintains contacts with militant training camps in Pakistan, including Balochistan.

There is also a logistics support depot near Shahgarh, about 90 kilometers from Kishangarh, that serves as launching pad for the Indian supplies and experts.

These were unimportant stations in the past but they have gained increasing importance since January 2002 when Balochistan became the hub of a new wave of foreign activity.

The method of transfer from India to Balochistan is simple.

Arms and equipment such as Klashnikov, heavy machine guns, small AA guns, RPGs, mortars, landmines, ammunition and communication equipment are transferred from Kishangarh and Shahgarh to Pakistani side on camel back and then they are shifted to goods trucks, with some legitimate cargo on top and the whole load is covered by tarpauline sheets. Arms and equipment are, as a rule, boxed in CKD or SKD form.

The trucks have to travel only 140 or 180 kilometers to reach Sui and a little more to reach Kohlu, a distance that can be covered in a few hours only. This is most convenient route because transferring anything from Afghanistan to these areas demands much sturdy vehicles that must cover longer distance over difficult terrain.

The small arms and light equipment are mostly of Russian origin because they are easily available, cheap, and difficult to trace back to any single source.

This route is also handy for sabotaging the Pakistani gas pipelines because the two main arteries of Sui pipe – Sui-Kashmore-Uch-Multan and Sui-Sukkur – are passing, at some points, less than 45 kilometers from the Indian border.

Whoever planned these camps and the subsequent insurgency, had to obtain initial help in recruitment and infrastructure from Indian RAW.

“When we first started the BLA thing, it was logical to ask for RAW assistance because they have several thousands of ground contacts in Pakistan, many of them in Balochistan,” said Sasha.

“Anyone wanting to set shop in Pakistan needs to lean on RAW,” added Misha.

The number of camps increased with time and now there is a big triangle of instability in Balochistan that has some 45 to 55 training camps, with each camp accommodating from 300 to 550 militants.

A massive amount of cash is flowing into these camps. American defence contractors – a generic term applicable to Pentagon operatives in civvies, CIA foot soldiers, instigators in double-disguise, fortune hunters, rehired ex-soldiers and free lancers – are reportedly playing a big part in shifting loads of money from Afghanistan to Balochistan. The Americans are invariably accompanied by their Afghan guides and interpreters.

Pay structure of militants is fairly defined by now. The ordinary recruits and basic insurgents get around US $ 200 per month, a small fortune for anyone who never has a hope of landing any decent government job in their home towns. The section leaders get upward of US $ 300 and there are special bonuses for executing a task successfully.

Although no exact amount of reward could be ascertained for specific tasks, one can assume that it must be substantial because some BLA activists have lately built new houses in Dalbandin, Naushki, Kohlu, Sibi, Khuzdar and Dera Bugti. Also, quite a few young Baloch activists have recently acquired new, flashy SUVs.

Oddly enough, there is also an unusual indicator for measuring the newfound wealth of some Baloch activists. In the marriage ceremonies the dancing troupes of eunuchs and cross-dressers are raking in much heavier shower of currency notes than before.

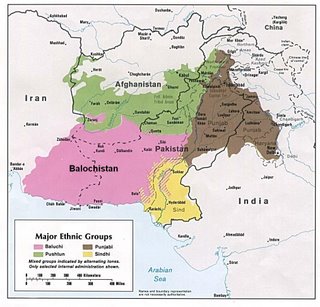

Based on the geographic spread of training camps, one can say that there is a triangle of extreme instability in Balochistan. This triangle can be drawn on the map by taking Barkhan, Bibi Nani (Sibi) and Kashmore as three cardinal points.

There is another, larger, triangle that affords a kind of cushion for the first triangle. It is formed by Naushki, Wana (in NWFP) and Kashmore.

Actually, landscape of Balochistan is such that it offers scores of safe havens, inaccessible to outsiders.

Starting from the coastline, there are Makran Coastal Range, Siahan Range, Ras Koh, Sultan Koh and Chagai Hills that are cutting the land in east-west direction. In the north-south direction, we find Suleiman Range, Kirthar Range, Pala Range and Central Brahvi Range to complete the task of forming deep and inaccessible pockets. Few direct routes are possible between the coastline and upper Balochistan. Only two roads connect Balochistan with the rest of the country.

Apart from the triangles of instability that we have mentioned there is an arc – a wide, slowly curving corridor – of extensive activity. It is difficult to make out as to who is doing what in that corridor.

Here is how to draw this arc-corridor on the map: Mark the little Afghan towns of Shah Ismail and Ziarat Sultan Vais Qarni on the map. Then mark the towns of Jalq and Kuhak in Iran. Now, draw a slowly arching curve to connect Shah Ismail with Kuhak and another curve to connect Ziarat Sultan Vais Qarni with Jalq. The corridor formed by these two curves is the scene of a lot of diverse activities and we have been able to gather only some superficial knowledge about it.

The towns of Dalbandin and Naushki where foreign presence has become a matter of routine are located within this corridor.

Different entities are making different uses of this corridor. Despite employing some local help, we could find very little about the kind of activity that is bubbling in this corridor.

We found that the Indian consulate in Zahidan, Iran, has hired a house off Khayaban Danishgah, near Hotel Amin in Zahidan. This house is used for accommodating some people who cross over from Afghanistan to Pakistan and from Pakistan to Iran through the arched corridor we have described. But who are those people and what are they doing, we could not find.

We also found that although Pasdaran (Revolutionary Guards), the trusted force directly under the control of Khamnei, are monitoring Zahidan-Taftan road, there is no regular check post of Pasdaran on the road between Khash and Jalq, making it easy for all kinds of elements to cross here and there easily.

We also found that the border between Afghanistan and Iran is mostly under the control of Pasdaran who come down hard on any illegal border movement and that is why the arched corridor passing through Pakistan is the favourite route for any individuals and groups including American ‘defence contractors’ and their Afghan collaborators who may have the need to go across or near the border of Iran.

Not surprisingly, part of this corridor is used by Iranians themselves when they feel the need to stir some excitement in Pakistan. Iranians also use the regular road of Zahidan-Quetta when they can find someone with legal documents as was the case with an Iranian who has business interests both in Pakistan and Iran and who came to Quetta just before the start of 7 Jan trouble. He has not been heard of since then.

There is a coastal connection that also provides free access for elements in Dubai and Oman to connect with militants in Balochistan. This is a loosely defined route but there are three main landing points in Balochistan: Eastern lip of Gwater Bay that lies in the Iranian territory but affords easy crossover to Pakistan through unguarded land border; 2. Open space between Bomra and Khor Kalmat; and 3. Easternmost shoulder of Gawadar East Bay.

Some Indians, a curious mix of businessmen and crime mafia, came in fishing boats from either Dubai or Oman and landed on the Gwater Bay in the Iranian territory before the start of 7 Jan eruptions. From there they traveled to Khuzdar and then Quetta where they met with some Baloch militants. It is rumoured in those areas that the Indians came with heavy amounts of cash but there was no way of verifying it. They were escorted both ways by some Sarawani Balochs who run their own fishing vessels.

Simultaneously, there were reports from our Washington correspondent that some ‘sources’ in Pentagon had been trying to ‘leak’ the story to the media that Americans and Israelis were carrying joint reccee operations inside Iran and for that purpose they were using Pakistani soil as launching point. The lead was finally picked and disseminated by Semour Hersh of The New Yorker.

However, from our own observations in the area we could not confirm this report although there is a possibility that the curving corridor that we have identified may have been used by the Americans and Israelis to travel from Afghanistan into Pakistan and then into Iran and back for this purpose although this is mere speculation, based on the movement of foreigners in this area, and we can neither confirm nor deny the substance of this report.

Also, there was some buzz, as reported by our correspondent in New Delhi, that some high circles were questioning the wisdom of two-faced policy of engaging Islamabad in peace dialogue while at the same time supporting insurgent activity in Balochistan.

It was also not clear as to why Iran would be interested in stirring trouble in Balochistan when it was faced by an imminent war from the American side and it needed all the allies it could muster on its side and one of those allies could possibly be Pakistan. It was also difficult to reconcile Iranian involvement in Balochistan with the fact that Iran-Pakistan-India gas pipeline, that is a crucial project for Iran, was in the final stages of negotiation and there seemed no logical point in sending mixed signals by creating difficulties in Balochistan.

Continued

No comments:

Post a Comment